Mahima turns her phone receiver toward her mouth, speaking directly into the headset so that the words come out clearly.

Confidently and purposefully, she speaks the name of her client's language: "Tigrinya".

The headset belches back an approximate response. "I understood: KOREAN".

Apparently that wasn't clear enough for the interpreter line. Mahima tries again, voice firmer: "Tigrinya!" The second attempt is more fruitful, and she's directed toward a Tigrinya interpreter who can help her client, Tanya, though she must wait another 20 minutes to be connected. Interpreters who speak Tigrinya aren't particularly common.

Mahima is helping Tanya retrieve a voucher to purchase reading glasses, and will review the different frames with Tanya to see which one she likes best.

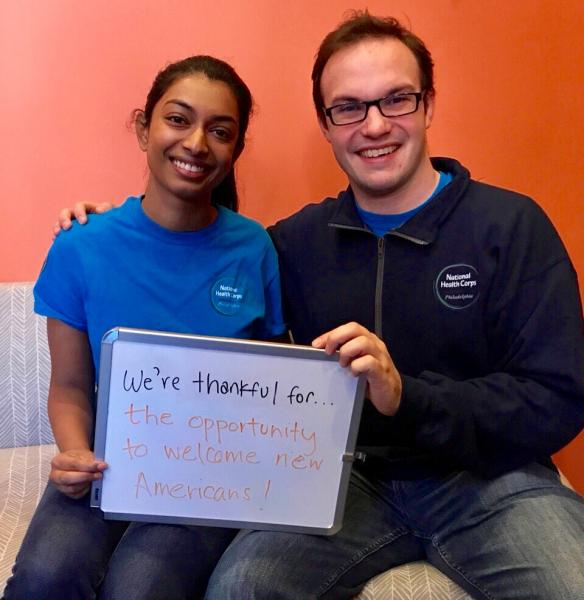

Alongside Mahima, I serve on the Health Access team at Nationalities Service Center, a local refugee resettlement agency serving Philadelphia. Our work places us at a unique junction between immigration and Health Access, and inhabiting space between the two can be maddening and bizarre. Healthcare is maddening enough on its own, even as a citizen of the United States, but when healthcare is overlaid with cultural and language barriers, simple tasks, like selecting glasses, become downright excruciating.

I've placed a 4-way phone call just to change a client's PCP. I've pushed back health screenings because the state department accidentally switched the month and day of a client's birthday on her official travel documents. When a physician asked for a medical history, I had to tell him that we didn't have one: the client had barely seen a doctor in his life.

The challenges working in refugee resettlement can be daunting, and it often feels like a Sisyphean struggle to keep our clients from falling through the cracks.

In the face of such large forces, it's hard to know how to help. How do you nurture those with no solid ground to stand on?

Working with Tanya, Mahima seemed to provide that ground by embodying it herself. As Mahima helps Tanya select glasses, she communicates with her presence, if not her words, that she is in Tanya's corner. This isn’t a solution to everything that ails Tanya. Tanya's immigrant experience is full of uncertainties and systems that are mercurial, and those systems will still be in place after she receives her glasses. Still, Mahima’s willingness to sit with Tanya on hold and wait for the appropriate interpreter provides Tanya with a powerful tool. Mahima’s presence is a reminder to Tanya that she has people she can trust, people who are willing to sit with her through life’s daily frustrations until they are overcome.

For now, waiting for the interpreter is frustrating and long, but Tanya is patient; she is resilient, and has spent much of her life waiting. And in this moment she doesn't wait alone. Mahima's dedication and presence are a reminder that she is welcome. After the call, Tanya will come back weeks later to pick her glasses up, overjoyed at her restored sight.