When I was a teenager, my first job was organizing and filing patient health records for a cardiologist neighbor. Always a curious young adult, I skimmed through the charts attempting to guess what the foreign sounding biological terms like “polypharmacy” “myocardial infarction” and “aortic dissection” meant. At this time, I also volunteered at my local hospital, where I often encountered patients who had undergone surgeries or other major health episodes such as a heart attack, stroke, or childbirth. These experiences shaped my early understanding of health as a collage of genetic and biological factors, something defined by individual behavior or DNA as opposed to their social or environmental circumstances.

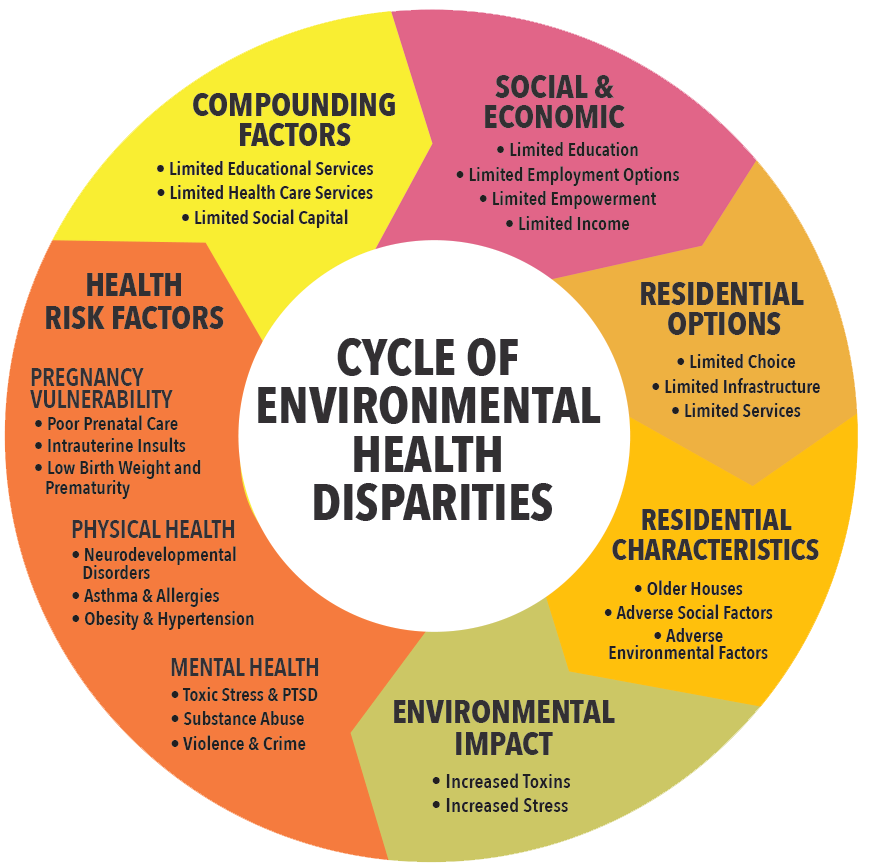

compound one another, often called the “social determinants of health”

From Science for Georgia.

I remember that this all changed when I listened to several lectures from Dr. Lisa Cooper of Johns Hopkins University in my senior year of college. Dr. Cooper’s work focuses on the health disparities that result from the intersection of identity factors (race, class, gender, etc) and social and economic policies that have historically (and deliberately) disenfranchised marginalized groups. Fascinated by this previously unknown arena of health, I began to realize that health is far more complex and socially informed than I had originally thought. One facet of the disparities field that I found particularly interesting was her research not only on health disparities, but healthcare disparities—that is, how patients experience health systems differentially across race, gender, class lines. One of her studies focuses on provider-patient relationships when controlling for race concordance/discordance (if the provider is of the same/different race than the patient). Some of her findings were that ethnic minorities rated physicians in race-discordant visits as more verbally dominant and less likely to engage them in making active decisions about their treatment (what she calls participatory decision-making). Her research also showed that patients in race-discordant relationships have shorter visits with less positive affect. (1)

As a white woman, a non-native Spanish speaker, an outsider to the community that I serve, I often internally reference Dr. Cooper’s research during my service term here at Maria de los Santos. Although I am not a physician, I realize that I am likely perceived as such to patients, since I am another professional figure in the clinic speaking to them about their health. Therefore, I try to utilize participatory decision making and patient-centered communication in every patient interaction that I have. Coherent communication is particularly important in consideration of the fact that I am speaking in my second language (Spanish) about 95% of the time. This necessitates that I take multiple measures to ensure that patients and I are communicating effectively. One area in which I have been able to strengthen my patient-centered communication abilities is in the provision of at-home colon cancer screening kits, commonly known as fecal immunochemical tests (FIT). When I first started giving out the kits, I was more concerned with adequately explaining the logistics--i.e how to complete the kit (I’ll spare you the details on that) with the demonstration tools given to us, where to drop it off, etc. However, I have learned that patients have been more likely to show interest and complete the kit when I spend a greater proportion of time communicating why the kit is important to complete because it connects to broader health maintenance and preventative health screenings. I’ve found that patients are more likely to ask questions not only about the kit, but also about other preventative screenings and other measures that they can do to be proactive about their health.

Maria de Los Santos is located

On the other hand, I’ve also learned that being communicative is not only about being in-depth—paradoxically, it’s also knowing when to step back and listen (this is especially considering the research I mention above, in which patients in race discordant visits rated physicians as more verbally dominant). For example, if a patient refuses to complete a preventative health screening or be referred to resources even if they are in need, I step back and don’t insist that they go through with whatever service I am offering. In one instance, I met with a patient who at first seemed suspicious of me and disinterested in talking about resources or completing a colonoscopy—even though he was overdue and at-risk. Instead of pushing the patient even further, I asked the client about what concerns he had regarding colonoscopies. Although he initially seemed distrustful of me, he ended up sharing that he was a caregiver for his wife who had Alzheimer’s and was worried that he couldn’t be away from her even during the brief amount of time he would be under anesthesia for the colonoscopy. After speaking about his current situation, he agreed to get a colonoscopy closer to the end of the year when he would have more family in town to care for his wife. This interaction for me reinforced the importance of participatory decision making. Through meeting the patient on his own terms, he and I were able to much more successfully address his medical and psychosocial concerns.

Like many other aspects of working in community health, my experience navigating and contemplating healthcare disparities has involved a lot of trial and error—when I look back on this year, I’m sure I will mark it as one of growing and learning as opposed to success--and I am grateful to have had the experience to create and develop equal partnerships with the patients at Maria de los Santos, the Fairhill neighborhood, and the broader Philadelphia community.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JekwZpo3eFs&t=593s