|

|

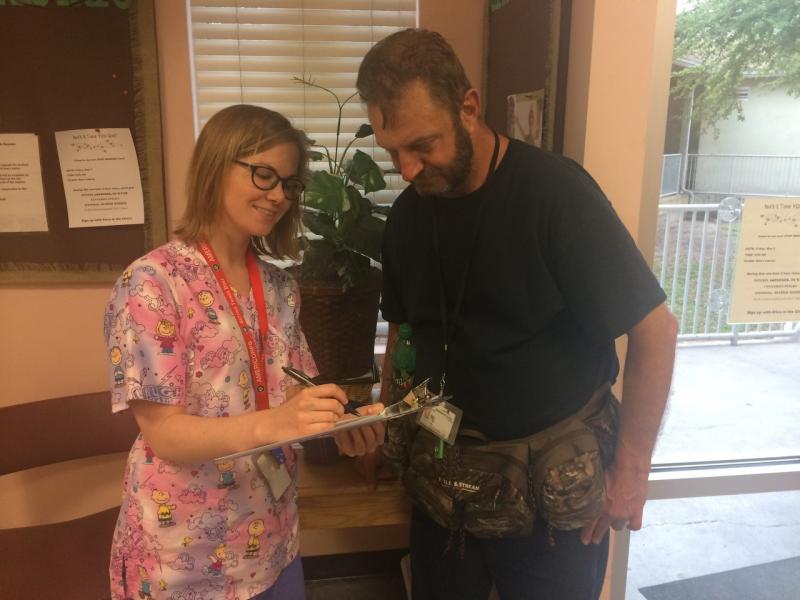

NFHC member, Erica, meeting with a patient to enroll him into Prescription Medication Assistance Programs so that he can obtain his medications at no cost.

|

Before beginning my service term with the North Florida Health Corps, I thought that I had seen poverty. I had worked with low-income and marginalized populations before, such as low-income battered women and Medicaid patients, but I quickly discovered that poverty went far deeper and affected far more people than I ever realized. After a few weeks into my service at the Sulzbacher Center, a comprehensive homeless shelter in downtown Jacksonville, I realized that our patients struggle with something that can't be described as mere poverty. To label the patients at the Sulzbacher medical clinic as "low-income" feels insultingly dismissive of the daily struggles they face. More accurately, it is the feeling of having nothing and being no one. It is a total lack of identity, connections, accomplishment, and comfort.

|

"It is a small but important drop in the ocean of services they need."

|

At the Sulzbacher Center clinic, my role is to enroll patients in patient assistance programs, which are pharmaceutical company-sponsored programs that provide free medications to very low-income patients. These medications are vital for our patients' daily survival: insulin, blood pressure medication, antipsychotics. Still, providing these medications feels doesn’t feel like enough. It is a small but important drop in the ocean of services they need.

Some days, my service position becomes frustrating and disheartening. I want so badly to see our patients find their way out of homelessness. I want them to have the lives they want -- employment, a safe and secure home, a feeling of stability. For most homeless people, though, this seemingly simple dream is

|

"In those moments, I feel as though I'm doing something right. It may not be enough... but it's something, and it matters."

|

almost impossibly out of reach. A shaky job market, poor health, mental illness, and the stigma of homelessness make it incredibly difficult for our patients to find a job and get on their feet. Every once in a while, though, a patient will turn to me and say, "I really appreciate your help. I don't know what I would do without Sulzbacher." In those moments, I feel as though I'm doing something right. It may not be enough, and it may not change a patient's life the way I'd like, but it's something, and it matters.