One sunny day at service, I trekked outside the Sulzbacher Medical Clinic and asked if anyone at the shelter’s patio wanted to enjoy a game of chess with me over lunch. It wasn’t long before a man of my age agreed, his lips trembling with his body as he struggled to find a way to communicate his interest. We sat and prepared the game—the incessant shake of his hands made it difficult for him to organize his pieces. His feeble state led me to doubt whether I was being challenged. However, after a handful of almonds and 15 minutes of intense play, his index finger awkwardly flicked his bishop to where my King would inevitably be dethroned along with my original judgements on his inadequacy. “Check mmmate.”

One sunny day at service, I trekked outside the Sulzbacher Medical Clinic and asked if anyone at the shelter’s patio wanted to enjoy a game of chess with me over lunch. It wasn’t long before a man of my age agreed, his lips trembling with his body as he struggled to find a way to communicate his interest. We sat and prepared the game—the incessant shake of his hands made it difficult for him to organize his pieces. His feeble state led me to doubt whether I was being challenged. However, after a handful of almonds and 15 minutes of intense play, his index finger awkwardly flicked his bishop to where my King would inevitably be dethroned along with my original judgements on his inadequacy. “Check mmmate.”

I played with many other residents after that first match. Sometimes I would lose and other times I would win. I soon began to consider my matches as a form of psychotherapy for the residents and myself.

Most residents at the Sulzbacher Center feel frustrated because of their dire situations. Some cope with their stress by acting angrily. I would argue that a fraction of their angered behavior stems from feeling inferior and unrespected in society, which makes them feel the need to prove their worthiness. Their competitive attitudes can lead to bitter interactions with others, which is one thing that I believe the game of chess can help mitigate.

During matches, I try to parallel the amount of verbal communication the residents provide, being respectful to their need for silence or conversation. Nevertheless, I always attempt to exemplify how to interact in competitive situations. For example, when we organize our pieces I make sure to ask where they would like for our queens to be in relation to our kings—already knowing the true answer and willing to go against the rule. This seemingly negligible gesture helps to promote their sense of entitlement in the game. Also, throughout the match, I stay composed in hostile situations and humble in those of triumph. Consequently, I gain their respect after matches; either won or lost, we shake each other’s hands with a smile.

Usually, we focus on the game at hand. This helps free my opponents from their lives for a temporary period of time. In tune with the benefits of art therapy, I encourage their imagination by often mentioning my fondness of the rook, passionately exclaiming, “If I could be any piece, it’d be that one!” They probably think I’m a lunatic, but I hope that I am at least projecting a method of coping with their stressful situations: imagination. Even so, while in play, we also practice a very vital skill to deal with their reality: critical thinking.

Usually, we focus on the game at hand. This helps free my opponents from their lives for a temporary period of time. In tune with the benefits of art therapy, I encourage their imagination by often mentioning my fondness of the rook, passionately exclaiming, “If I could be any piece, it’d be that one!” They probably think I’m a lunatic, but I hope that I am at least projecting a method of coping with their stressful situations: imagination. Even so, while in play, we also practice a very vital skill to deal with their reality: critical thinking.

This year I have learned what systemic poverty is like—educationally, locally, etc. As a result of my experience and understanding, I think it is pertinent for the impoverished to maximize their problem solving abilities. Unlike life, chess starts with opponents at an equal position. With this in mind, players begin the game knowing that they are in total control of their pieces and thus can only blame themselves for how they deal with the problems their opponent presents to them. During our matches, the residents and I practice our decision-making abilities by critically thinking through the consequences of our every move, at times thinking multiple moves ahead. The critical thinking in chess is great practice for the necessary critical thinking in life. For example, while a resident considers robbing someone, they could be thinking prospectively about the legal and moral risks that result from committing such an act. After enough play, the game of chess can promote the mantra: will this decision really better my situation?

I hope the mantra sticks as much for them as it surprisingly has for me. Chess reminds me to live in the present in hopes of a better future, withdrawing from the past as with other unchangeable factors in life. The game of chess makes me question my critical thinking. Even if my beloved rook is overtaken, should I dwell on its irrelevancy in bitterness? No. Even though I imagine something to be of great value, I can also choose to disregard it and consider all of the other pieces I have left to move. For example, the queen can act as a rook and more! One man I played against, an amputee veteran, epitomizes this schema in real life. Having lost a leg, the man uses his able hands to enjoy something he can still do: play chess.

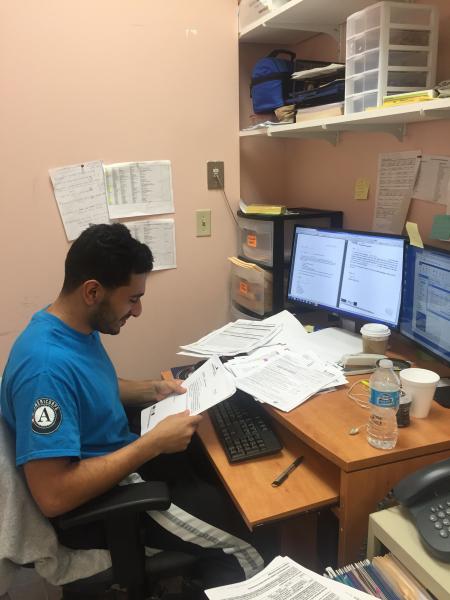

This blog post was written by NHC Florida member Amir Dada.

Amir serves at I.M. Sulzbacher Center-Medical Clinic as a Patient Navigator.